Oral Tradition — The Living Heartbeat of Our Denesuline Culture

“Myths are public dreams, and dreams are private myths.” – Joseph Campbell

In this chapter, I write about oral tradition as the heartbeat of our Denesuline culture.

Oral traditions are the living foundation of who we are. Long before our people read or write, we were masterful historians, philosophers, and scientists of the land. We passed knowledge from Elder to child. It went from heart to heart and voice to spirit. These stories were never just entertainment. They were teachings: our law, our maps, our medicine.

In our family, storytelling was sacred. As a child, I would sit quietly, listening as my older siblings and elders spoke late into the night. They told of how the world came to be. They shared how to live in balance with the land. They also spoke of the prophecies that guided our people through times of darkness. We listened with our whole being. To interrupt was not just rude — it was to risk missing a thread of sacred knowledge.

Roger and Peter, my brothers, were a keepers of the Dene prophecies. They told stories that had been passed down through generations. These stories spoke of times when the land would change. They described how we would survive. Peter taught us through his humor, his presence, and his firm belief in our teachings. Dora kept the language alive by insisting we speak Dene in our conversations. She grounded us in the rhythm of our ancestors’ tongues. Annie, with her generosity and kind nature passed on stories through food and stories of our grandparents.. Each sibling held a different strand of the web. Together, they taught me that oral tradition is not only spoken. It is lived.

Our language is key to these traditions. Dene is not just a way of speaking, but a way of being. It expresses things English can’t. We are not separate from nature — we are part of it. To speak Dene is to understand your place in the world in a deeply relational way. Colonial systems sought to erase our language. They were not just stealing words. They were severing our connection to the world. And yet, in our home, the language endured. Even now, I speak it proudly, knowing that each word carries the breath of my ancestors.

I often think about how our mother, Therese, knew exactly when a story needed to be told. She never said, “Let me teach you something.” She simply began. By the time she finished, the lesson was planted like a seed. That is the Dene way.

When my son Andrew was a baby, my mom came to visit us. We set up a camera in front of her as she beaded. From time to time, she would tell a story or share a memory. Those moments were quiet, beautiful, and precious — her voice offering teachings in the most natural way. Knowledge was passed down like this: not forced, not formal, but flowing like a river through daily life.

Even today, I carry the rhythm of those teachings in my voice. Whether I am writing, speaking to youth, or sharing knowledge, I know the stories flow through me. They are not mine alone. They belong to all of us.

I do not partake in Cree ceremonies like sweats, and neither did my parents. My mother and father never participated in sweat ceremonies. They said it was not the Dene way. Our teachings came through story, through language, and through daily living — not through that particular practice.

The teachings of the Dene, when first spoken, are not always clear. As children, we listened, but we did not always understand. With time and experience, the lessons revealed themselves. A story told at ten years old carried one meaning; the same story told at thirty carried another. This is the way knowledge deepens, unfolding like layers over a lifetime.

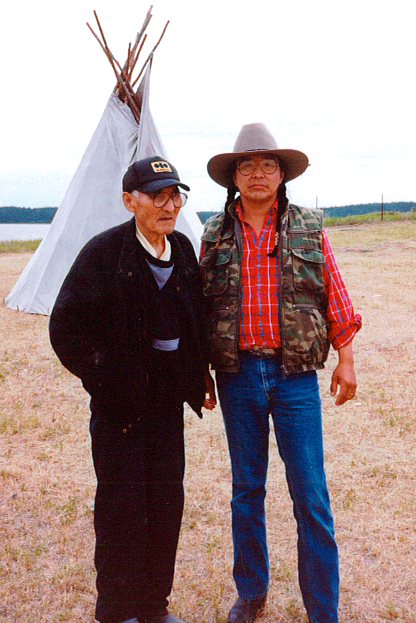

This is how we remember who we are. This is how we survive. my brother Freddy with my dad Isidore Deranger

We are the stories. And we are the tellers.

Leave a comment