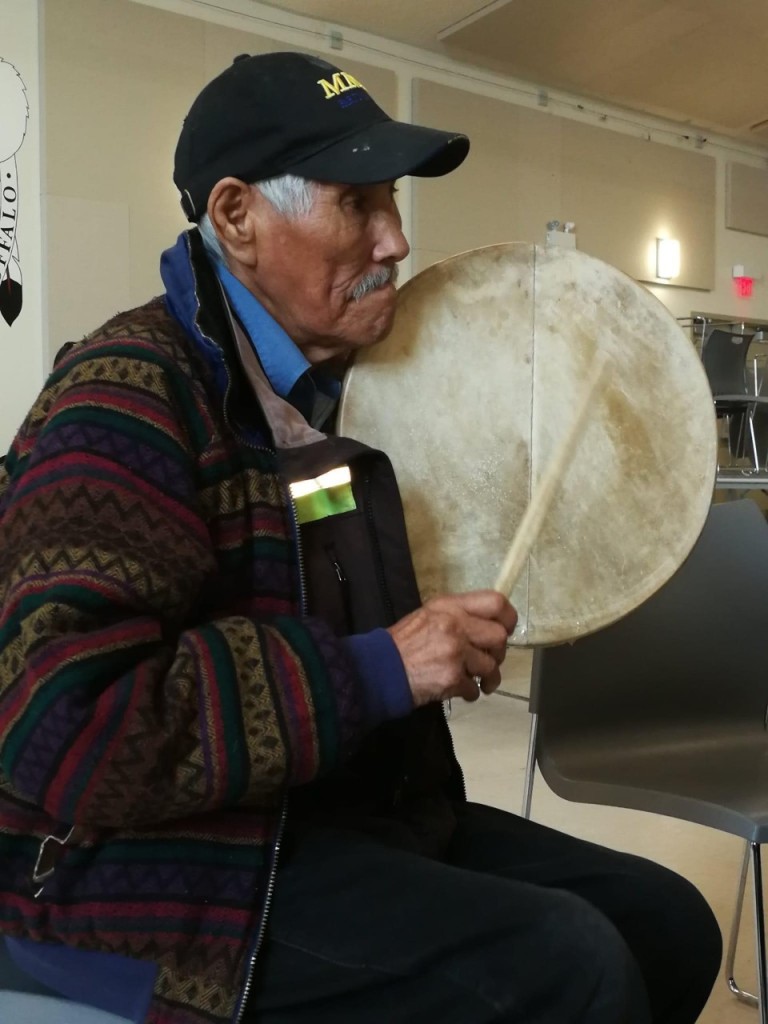

Dene Youth drummers

There is no worshiping of idols, or of a God, only the deepest respect and appreciation for Natural Law. What that means for me, as an Indigenous person is to respect nature, the trees, the water, the wind, the sun, and all living beings, the bears and birds to name a couple. This is the way of the Denesuline, my people.

My belief is that being a true Indigenous person means honouring the teachings of the Dene, my parents, my grandparents, and my ancestors. We share our story through our drum. I established a Foundation to uphold these teachings at [sevethgift.ca](http://sevethgift.ca)

My parents didn’t attend residential school and continued to speak Desuline and to practice our culture at home. I am privileged that I experience this childhood.

I have always understood spirituality as being in harmony with nature, a lesson I observed from my Dad, Isidore Deranger and other Dene who lived in the hamlet of Fort Chipewyan, Alberta.

I spent seven years at Holy Angels Residential school in northern Alberta, I was not beaten, starved, abused. I am grateful that I was born a generation late for those types of abuse.

I attended Holy Angels Residential school in the mid-60s and 70s, approximately 15 years before the building was demolished. When I was a student there, the culture in the mission was unlike in its earlier years. Perhaps it was because a young priest from France, Father Gilles Mousseau OMI or the changes in the church doctrine after Vatican II, but for whatever the reason, I was spared some of the degradation that former students, including contemporaries of mine and some of my own siblings experienced.

At the time I was there, the young Father Mousseau was instrumental in making some positive changes. We, who lived in the hamlet of Fort Chipewyan, were allowed to go home on the weekend for a couple of hours each week on Sunday. We were allowed to keep speaking our native languages. Several nuns and priests learned the Dene (Chipewyan) or Cree languages. I continued to have a friendship with Father Mousseau until his death in the early 2000s. He was a rare exception in his tolerance and open-minded attitudes.

I have come to understand that it is acceptable to speak the truth about my positive experiences, even in an institution designed to “kill the Indian” in me, as documents on the origins of the residential school system openly state. I have also acknowledged that many former students were not so fortunate and had horrifying and devastating experiences, some from my own immediate family.

Lately, as more former students become comfortable in telling their truth I discovered that two former students from Holy Angels were committed to a mental institution for nothing other than not being compliant or running away home. My older sister, Rosemarie, was one of them. Learning about this I wondered, how many more former students were sent away to a mental institution for no reason, to be stigmatized as mentally ill? The trauma they experienced would follow them most their lives.

On June 24, 2021, the remains of 751 students buried in unmarked graves at Cowessess First Nation were identified using ground penetrating radar. This was after the discovery of 215 remains at another former residential school in Saskatchewan. Both of these discoveries, the first one in BC and the latter in Saskatchewan, touched many people’s hearts. Many tears have been shed by people who were not in residential school at this confirmation over what many people might have regarded as unfounded rumours. But after the sorrow we are left with questions, many questions.

The disbelief and horror of the remains of 215 children, some as young as three years old, is amplified with the news of another 751 remains discovered last week. Nearly 1000 unmarked graves in only two of Canada’s many residential schools! There can be no denying that something unthinkable happened to these hundreds – and in all of Canada perhaps more thousands – of children. The question then becomes: what do we do about it?

It is inconceivable to me that no one knew what was happening in those schools. But of course, some knew. Estimates have been made that thousands of unmarked graves exist in the grounds of former residential schools. These estimates – mere statistics – did not move people, as I thought it would. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission sought an addition to its mandate to get better data on child graves at the sites of former residential schools. The federal government turned them down.

I am convinced that as more ground penetrating radar work is being conducted, more bones on former residential school grounds will be identified. I pause in silent contemplation of this horror. This is Canada! We have a right to be angry. We can be wounded, accountable and compassionate. We can grow and heal as we move on as a society.

The Church knew, and the federal government of the day certainly also knew. Hundreds if not thousands of people in the communities must have repeatedly demanded answers why their babies didn’t make it home. My own mother put her 14 year old son on an airplane to the hospital in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. She never saw him again. His remains were never sent home. Is he in another unmarked grave, waiting for ground penetrating radar to discover his bones? I never met that brother but I did witness the sorrow my Mom carried to her death. The many occasions she worried about us when we weren’t home. She cried many tears for a son she could not put to his final rest in her community.

The Catholic Church does not hold to an Indigenous spirituality or humanity. The Church called us savages. Mentally, emotionally, and sexually abused students who were in their charge. They followed a policy to eliminate our Indigenous identities. They were negligent, and they did not provide basic care. They treated us as if we were disposable, not worthy of normal human dignity or their compassion. Their actions literally killed us.

The government of Canada, always penny-pinching when it came to Indigenous peoples, did not provide adequate nutrition or medical care. They did not provide the basic human care to the bodies of students who passed away in residential schools be sent home for a proper sacred burial or consider their families’ need for closure. Instead, they buried them without ceremony in graves on the property. All this callous brutality in the name of “civilizing” our people. Ironic isn’t it, being they are Christians carrying out the teachings of Jesus.

The Government of Canada ought to designate annually a month to the remembrance of children who perished in residential schools. It is the least they could do.

WHAT DO DO NEXT?

1 DESIGNATE JUNE AS AN INDIGENOUS HEALING MONTH

2 FUND INDIGENOUS CEREMONY IN EACH COMMUNITY TO HONOUR THE CHILDREN

3 DEVELOP K-12 CURRICULUM TELLING THE TRUE STORY OF RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS IN CANADA

4 CULTURAL HEALING ACTIVITIES IN EACH OF THE FIRST NATIONS ACROSS CANADA

5 DNA TESTING TO IDENTIFY FAMILIES OF THE STUDENTS FOUND IN UNMARKED GRAVES

An Indigenous Health Month would be filled with Indigenous cultural activities, including the development of curriculum in K-12 in the schools identifying, and telling the story of residential schools in Canada. That is how we should honour the students who perished in residential schools across Canada. To that end, funding should be provided to all First Nations across Canada to develop this curriculum and create a campaign in their communities in honour of residential school children who died. This is how we take back what was lost and move away from victimhood and retain agency in all our lives.

Leave a comment