-

THE FAMILY I CHOOSE

family picnic in an Edmonton park. The saying goes that we don’t pick our family, but we do pick our friends. I question that!

Sisters

L to RIGHT Dora, Rose, Liz, me, Mary, Annie 2016 Cahiron

Said another way, I believe that our soul, our true essence, picks the family we are meant to be born into and we decide how living within our family can help us to show up powerfully in life. You can be either a victim or a warrior. Further, I also believe I picked the best time to be born. I feel fortunate to be part of a family who shaped my character.

As Indigenous people, we are an extension of the natural world. There is a saying that we on some level pick the family we are born into from the spiritual realm before we are born. And I reflect on what being a Deranger teaches me. I am guided and inspired by my family and the lessons I am taught helps me move through life with grace.

As an Indigenous person, I believe that our genetic code and both the impacts of trauma and our challenges are transferred to us over seven generations. And in each generation we overcome weakness and learn lessons in this life. Which begs the question, why did I pick this family?

That said the study of astrology does point to something called cahiron, which are the lessons we are meant to learn in this life. Have you ever heard about an old soul; some people who appear to have lived many lives? The Buddhists believe we are reborn until we learn the answer to our suffering. It is our karma until the lesson is learnt.

Reasons

Taking this perspective as I do, gives me strength in how I respond to my life .

I chose the Deranger family. Instead of thinking it was random that I was born into this extraordinary family. Because it puts me in powerful position in that nothing in my life is done to me.

When I start from the position I choose everything in my life, even my family, means I don’t have room to blame anyone for how life treats me. I must learn from my experiences.

Background

Coming from a large Indigenous family, we were not wealthy in material things. However, we have something far greater, we have the guidance and protection of our ancestors. We have family who are caring, and lighthearted. My family taught me to be confident in my own skin.

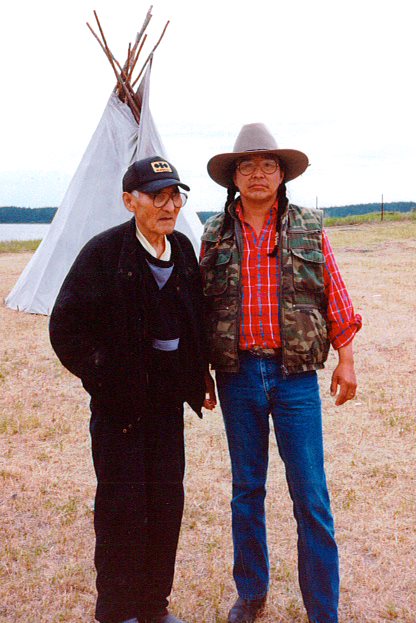

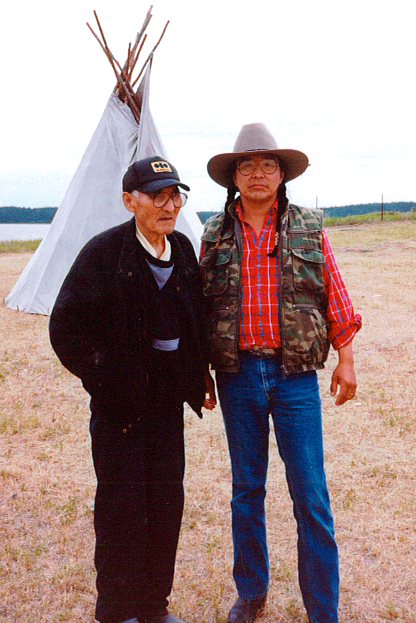

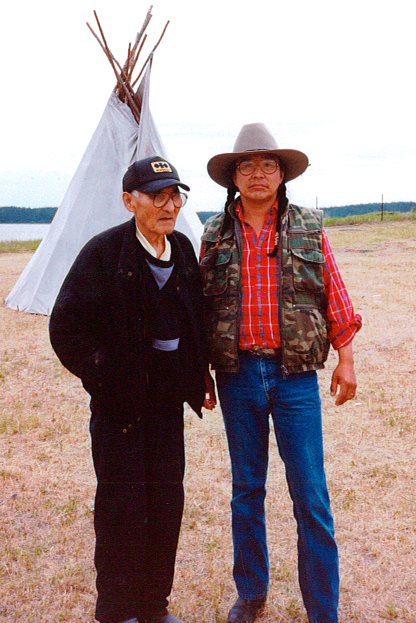

Isidore Deranger my dad 1909-1992 Context

Deranger Family

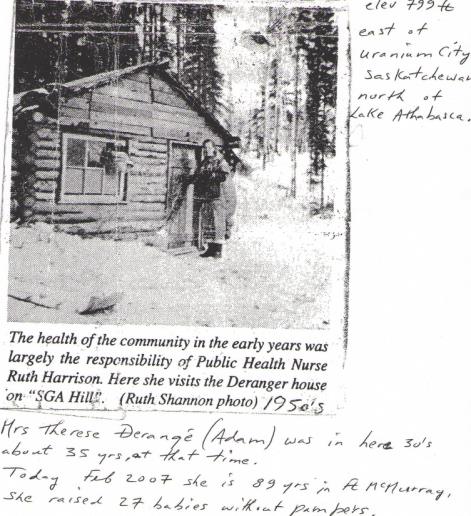

My chosen family (of 16 children) in a Dene Indigenous family lived in Northern Saskatchewan before I was born. They lived in Uranium City (where I was born), then moved to Fort Chipewyan, and Fort Mcmurray in Alberta. In Fort Chipewyan we lived In a small hamlet without electricity or plumbing, with a mixed population of Dene, Cree, Métis, and people of European origin.

Let this sink in. I was raised with ten brothers, five sisters and our two parents in a one-room log cabin before we moved into a bigger house.

By and large it was a Roman Catholic household, but thankfully, my father Isidore was deeply rooted in our Denesuline culture of natural laws of nature. We are connected to our ancestral lands. My late brother Pat’s ashes were buried on our land, Denekizi. And the ashes of my late brother Roger, who passed on December 7, 2024 (incidentally my birthday) will be spread there this summer.

The final resting place of elder brother Pat Deranger (1951 – 2019). RIP The distinction between our worldview and that of the colonizers is the notion of good and evil, because within an Indigenous worldview there is no such thing as good or evil, heaven or hell, sin, or sinners. These do not exist in our reality. This is a Roman Catholic church construct designed to control their congregation.

Little me in front of our log cabin in Uranium City After all, we don’t ascribe sins to flowers, birds and other wildlife. The RC believes that a newborn is already a sinner, We exist like nature. in nature, and we are interconnected, and interdependent on one another. That is the Indigenous wouldview.

Recently my older brother Jimmy said, our culture is tied to the caribou, and our language. We were nomadic peoples. It is vital that we speak our Dene language, think first in Dene, he says. We Dene continue to utilize our traditional lands in all direction. And we always give offerings to the land and water.

When my ancestors hunted, fished or trapped they thanked the wildlife for giving their life for our food and we shared our food with our community. Our connection to the land is sacred.

The language we spoke at home is Chipewyan (Denesuline), a Dene dialect. My father was a hunter and trapper, and my mother made beautiful beaded Dene jackets, gloves, and moccasins for the family.

The last jacket my mom made for my son, Andrew There are no words to describe how I feel about this family, other than it is a blessing to be on this journey with my siblings and as one of the youngest, and the youngest female. I have always felt cherished and protected by my family.

I am truly blessed. There are a wealth of lessons to be learned growing up in a large Indigenous family of acceptance, compromise, and diplomacy, which led to me being tenacious with an unwavering spirit.

Our mother was a complex person. She was both firm but could be flexible. She was incredibly demanding and determined. But she was also generous, caring, and funny. Even though we had a full house she made room for other children who needed a safe place.

My mom, older brother Rossi (1957-2016) and me In turn, I stood for being the best daughter I could be for her, as I matured. I loved her unconditionally. Each time I thought of her, my heart would fill with pure joy and love for her. Even now 8 years after her passing I feel the love I have for her. I can honestly say that we’ve had an extraordinary relationship. I saw everything she did through the lense of my love for her and her love for all of us.

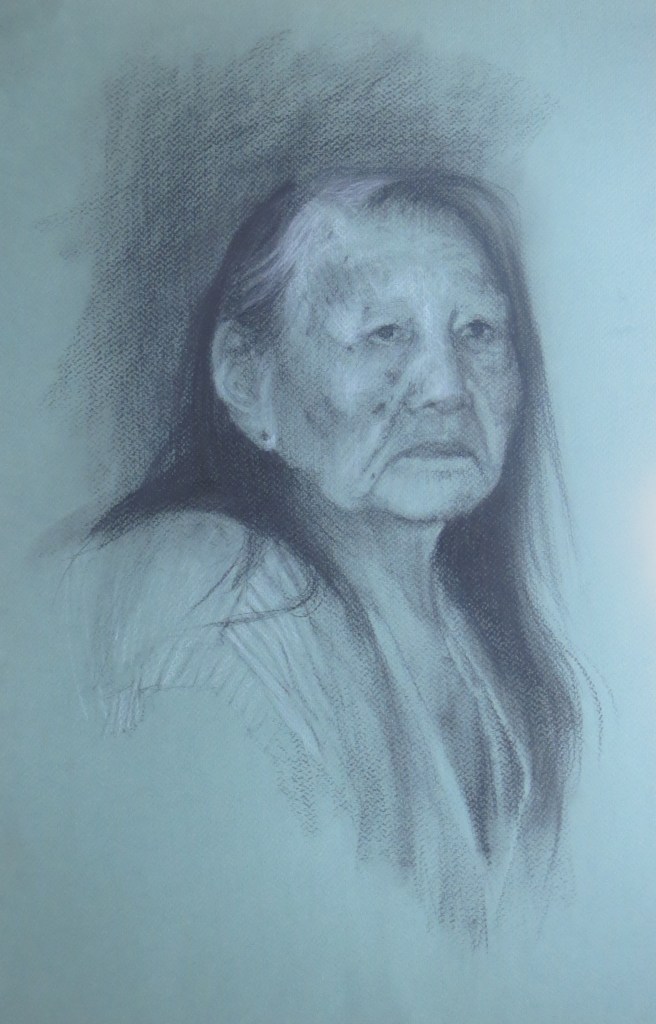

My mom’s likeness done by artist Margaret Ferraro. com

My mom Therese Deranger (1919-2016) The lessons I learned from my Deranger family are

- Speak up when an injustice occurs — which is why my career was in Indigenous land claims.

- Love unconditionally

- Don’t be afraid to take risks

- Accept the knowledge link to our ancestors is strong and they are always close beside us helping and protecting us

- Remember the words of the elders

- Respect all living beings

- Show up in life, listen and be present

6 generations matriarch

My oldest brother Peter (left) and my late brother Roger (right) (Denekizi)

Our traditional land – home of Dene Kizi Academy Land based teachings

Dene Kizi Academy 2022

Future traditional knowledge keepers

Mom and sons and other male descendants on her 90th birthday. -

Life peppered with Gratitude is a life worth living

On the Ottawa River on a friend’s boat Being happy means living your best life and not being afraid that others see it.

legends say that hummingbirds float free of time carrying our hopes for love, Joy and celebration. The hummingbird’s delicate grace reminds us that life is rich, beauty is everywhere, and every personal connection has meaning. laughter is life’s sweetest creation.

Being authentic, is not always the easy, Being happy means living my best life and not being afraid to let others see me.

Recently someone asked what I do. I responded I am a writer, a blogger she asked are you an influencer. I said no, I’m not an influencer, however I do have a blog and I am the host of Empathetic Witness Podcast with Angelina. If I inspire others to live their best life it makes me happy.

The moments of my life are not staged for social media. Gratitude highlights the positive in my life, and happiness is being present for those moments.

You, and only you, decide how you will react to situations either of your own doing or someone else’s actions. You decide how you will react . It is simple. Don’t make it complicated. If you want to be happy, you can be because you’re in charge of your feelings. all it takes is a change in perspective.

Some situations will take more effort on your part, like a muscle you need to exercise. Remind yourself when you notice your reaction can either hurt or give you peace and change the story.

For example, A regret I had years ago when I did not support a friend, and I felt she felt betrayed by my actions. I later called her to apologize. She understood why behaved as I did, and she said she was okay. A big-hearted response, and it changed my story of the event. I realized in that moment that it was my own perspective that was making me feel badly.

Being 100% authentic, may not always be the easiest route to take. I am grateful to have family who are not afraid to have a good belly laugh and live life not taking themselves too seriously.

My cousin

My sisters!

My sisters enjoying a joke! -

Navigating Life

Ottawa River I’m sharing something very personal, a challenging situation I have had most of my life, because I hope that both my struggles and my insights may be of use to you in your life, in some way. In fact, This by far, is the most vulnerable thing I’ve ever shared on a social media platform in the hopes that something about my journey will support you on yours.

For those of you who don’t know, I am a blog writer, podcaster, and the founder of a charitable foundation, seventhgift.ca I’ve held executive positions most of my career.

I had poliomyelitis (polio) as a child, shortly after I started walking. I know that a lot of folks might not know much about polio because it’s been nearly eradicated over the last 65 years. But as a child when I got hit with it, polio was one of the most feared diseases on the planet. You might even question, how I got polio when the polio vaccine was available before I was even born. I am Indigenous; and my parents lived in an Indigenous community. Need I say more?

In those years, polio was killing thousands of children worldwide every summer and paralyzing tens of thousands more. The numbers were in the millions.

We can celebrate that rates of polio have dropped phenomenally around the world since then. In recent years, there have been only a few hundred cases per year of polio in the entire world, mostly in 3rd world countries like Pakistan and Afghanistan.

I have no memory of the incident except what I’ve been told. One day I was paralyzed, and I couldn’t walk. And after a while, the feeling and movement began slowly to return. But the process of regaining use of my legs was slow, and only after many surgeries I was able to walk again.

In the 60’s and 70’s polio was treated by orthopedic doctors because there was little experience understanding that it affected the motor neurons in the spine. I was fitted with long braces on both legs, but eventually only need a short brace on my left leg.

When I entered adulthood, the prognosis was that I would never walk normally, or run due to weakness and discrepancy in my left leg.

After a partial stroke in 2018 I decided to update my brace. it had been over 20 years since I had a new one.

My stroke doctor, who I respect, referred me to an orthopedic specialist, who refused to give me a prescription for the type of brace I had as a child, one which allowed my ankle to move as I walked. She said that with the weakness in my left leg this brace was not suitable for me. When I allerted my specialist, he said he couldn’t do anything about it. He replied to my email when I brought it to his attention saying:

“This Dr. is my department’s expert in this field and you have been seeing her. I’m not passing the buck, but should not this be going to her?” “

She told me clearly, I will not give you a prescription for the brace you want. What was I to do? I felt defeated. Based on research and decades of experience dealing with my challenges, I was convinced that the current rigid brace she recommended would only create complications for me down the road, as I got older. My research showed that a movable ankle is necessary to lubricate joints in my leg, my knees, and my hips. We are not meant to be in a unmovable brace, it is not natural. In 2023 there must be braces that are supportive and yet allow for some natural movement.

I saw my GP, who fortunately understood what I was asking for and, he provided a prescription for a hybrid brace, a mix of a rigid and movable ankle. The process took me two years and now I have exactly the brace I wanted and needed (see the photo). Indeed, I have captured some independence, I feel as though I’ve got my life back to some degree. I recently saw a professional who confirmed that my hip joints were stiff and not rotating in a natural way. I need to mitigate further damage in my hips, and I believe this brace in part is how to do that.

Developing Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS)

Poliovirus Then and Now

I developed post-polio syndrome, or (PPS) when I was 32, and to that point I had not heard the term despite living so many years with polio. You may never have heard of post-polio syndrome, either, and this is true of most physicians too. A significant percentage of the people who got polio and survived, and particularly those who worked extra hard to achieve things despite having been stricken with the disease, have suffered later in their lives from this condition. To add to the complication of PPS, I suffered a partial stroke during surgery in 2018. I have trouble walking; it is not clear how much is related to stroke or the PPS.

The medical literature says this about PPS. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6371137/

It affects between 25–40% of polio survivors. And unlike polio itself, PPS is not contagious. But PPS is serious. Parts of the body that regain movement after being paralyzed by the original polio can again become paralyzed.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-polio-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20355669

Nearly all polio survivors who develop PPS do so within 15–40 years after their initial polio. When I first noticed symptoms, I was told it was age related and that everybody loses muscle strength. I was 32.

I’m doing the best I can with it, including getting as much exercise as I possibly can, which is a challenge when your legs don’t work well and you worry about falls. I believe in doing all I can with what I’ve got. And, of course I’m doing everything I can that might help me to retain as much quality of life as possible, which is why I fought to get the brace I knew I needed to give me quality of life.

I’m listening, in every moment that I can, for what I can learn and what I can love on this journey. In fact, when I start to feel depressed or start to feel sorry for myself, I will often think about Viktor Frankl and what he endured, and yet he came out on the other side whole . Or I’ll recall some of the things I love. Not just the things I like — that just wouldn’t be enough to shift my energy. But the things and the people I truly love. Like music, reading, writing, and having a purposeful life.

I’m going to be honest. was not all sunshine and roses, especially having to work hard against conventional “expert” medical thinking to get a brace I knew would make my life better. What I have learnt is no matter the challenges, one must look first to give meaning to it, and then move into action to improve their situation. As an Indigenous person I am carried on the backs of my ancestors.

I am my own avocate -

WE ARE NOT GARBAGE; SOMEONE KNOWS SOMETHING And CHOOSES TO REMAIN SILENT

In this blog are my thoughts on the matter of Missing and Murdered Indigenous women in Canada. (MMIW) Caution: reading this blog may be triggering to some.

My intention for writing this blog Is to motivate and inspire you, the reader to want to make a difference in this matter. You might think, how can I make a difference? I have some suggestions below on how you can help. Don’t disappoint me, please. Comment if this topic makes you think or do you remain indifferent.

First, I am an Indigenous woman from northern Alberta. If I went missing, I am confident my family would be concerned and would look for me. Not because I am educated, and a contributing member of society who pays taxes, but because I am a human being, and I matter!

My point is it shouldn’t matter if I were a drug addict, homeless and or earning a six figure income for people to care if get murdered.

My Connection to two victims

I imagine, because of the large number of missing and murdered Indigenous women, there must be several people in Canada who have been touched by either knowing someone who is missing or knowing of someone who is related to someone who is missing or has been murdered.

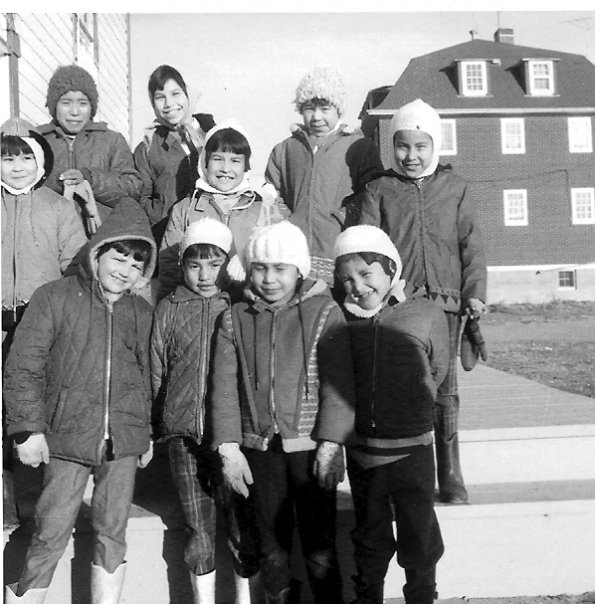

It is interesting being that I am from a small hamlet of less than 1500 people, and I know TWO Indigenous women who were murdered. A childhood friend first went missing, and then was found murdered in the United States. She was my classmate at Holy Angels Residential school in Fort Chipewyan, Alberta. I remember Sandra as a young girl with a beautiful smile. She was smart too. Years later, I had heard she made some questionable choices in her young life. One summer, she made a fatal mistake. She decided to go hitchhiking into the United States and was not heard from again.

Much later, her family received a call from the RCMP with devastating news that was delivered by phone, not even in person. The officer described how her body was dismembered and disposed of in garbage bags. Her DNA sample was the only way she was identified. Her killer is a person who picked her up and gave her a ride and was never convicted of her murder. Sandra was only 24 years old.

Ms. Amber Tuccaro, whose killer’s voice was heard on a chilling cell phone recording linked above is just one piece in a RCMP investigation, was also from my community, and was the daughter of my older brother’s classmate. We owe it as a society to care and to take some sort of collective action. I challenge everyone reading this blog post to do something. Write the PM’s office and demand he does something about the missing and murdered Canadian Indigenous women and girls. At the very least, share this blog on your social media. Do not underestimate the power you have to make a difference.

If we remain silent, our collective inaction speaks volumes about who we are as a society. The message this sends is loud and clear to me and perhaps to the murderers living freely among us, that Canadian Indigenous women and young girls can be raped, killed, and disposed of like garbage. When did our society become so indifferent to the violence against Indigenous women and girls? That is a rhetorical question because since colonization very little value has been placed upon an Indigenous person’s life.

It must STOP. Where is the outrage?? We need answers! They were human beings, members of our society. We should have protected these Indigenous women.

Sadly, we continue to hear stories of the discovery of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in 2023 and it will continue until we change our attitude about Indigenous women .

Are you interested enough to ask the questions?

- Who is doing this to the Canadian Indigenous women and girls?

- How many murderers are walking among us?

- Where are the bodies of these women and girls? If nothing else, we need to put them to rest by finding the bodies and bringing them back to their families for a proper respectful burial.

- How can you help

Consider if someone is murdering women and girls it could be someone you know. Even more of a concern, since this is not an isolated or regional matter, and is happening across Canada. There could be many murderers among us. Many Indigenous women have disappeared on the trail of tears highway in BC.

Recently Canadian serial killer Paul Bernardo has been in the news because he was transferred to a medium security prison. I remember in the 90’s, at least 3 people knew it was Bernardo who was raping and murdering teenage girls. These were Caucasian girls.

It makes me angry that as recent as this week an Indigenous young woman’s body was discovered in a landfill, discarded, like garbage. It is incomprehensible the outrage is only coming from Indigenous communities. It reinforces the belief that there is little value in an Indigenous woman’s life. Am I wrong?

Amber’s dismembered body was found in a ditch in Alberta the summer of 2012, Over 20 years ago, two years after she went missing. RCMP are appealing to the public to identify the voice in a recorded call from a cell phone. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6mEeyd1sF6g Her murderer was never found.

A woman’s body was recovered from Winnipeg’s landfill on Monday July 17, 2023, the second in 10 months, with more believed to be buried.

The landfill is currently closed as police continue to investigate after 33-year-old Linda Beardy’s body was discovered at the beginning of the week. It should never be reopened as a landfill. “It should be turned into a memorial site because we know that there is more,” it was reported to CBC Manitoba Information Radio host Marcy Markusa on Thursday. In the context of this society bodies of murdered Indigenous women will be dumped if not this land fill, in other places where it would be as difficult to discover.

The truth is I am at a loss. I realize anger doesn’t help but is it enough to motivate you the reader to do something? What would it take to see a modicum of emotion and compassion about these girls and women from you? Well, to be fair, I do believe you care, how could you not care. However, I am not as sure that the enormity of the situation is really appreciated. Until you have personally experienced a loved one murdered you cannot fully understand the anger, the grief, bargaining and acceptance. Let’s say I was able to reach you and you ask the question what can you do? The first thing you can do is get on social media with the hashtag Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women #MMIW. Share this blog with your network encourage them to get on social media with the hashtag #MMIW.

The question remains, where are they? The conservative numbers of missing and murdered women is over 5,000. If your family member disappeared, what would you do to bring awareness.

What Next?Mr. Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, does it matter how many more must be reported missing or found pulled from dump sites, having been murdered? The Prime Minister has many priorities, but this must be one of them. The conversation around the discovery in a Manitoba landfill is disgusting, it is about the cost and manpower to continue searching the landfill, so they gave up leaving the enormous task to the Indigenous people. Sadly, I can’t be convinced it were a Settler, a non-Indigenous woman the conversation would be on cost. Nonindigenous women would be concerned that a murder is out there. They would organize themselves so they would be protected and safe. I am afraid the truth is there is virtually no value placed on an Indigenous woman’s life.

Why are the Prime Minister of Canada (PM), Royal Canadian mounted police (RCMP) desensitized to the plight of the surviving families, the parents, the siblings, and the friends of the Indigenous women who have disappeared or been found murdered?

Remember the Pickton murders in BC? Police were informed there may be a serial killer preying on indigenous women from Vancouver’s lower East Side. These concerns fell on deaf ears. It begs the question can Indigenous bodys be more dishonoured, in a landfill or given to pigs to be eaten so the evidence is destroyed. Both are equally disrespectful. Let’s not forget the Gladue case in Alberta. Thankfully, in that case the murder was charged.

In 2014, the Canadian premiers unanimously supported the request for an inquiry. Finding the body of Ms. Tina Fontaine had renewed the call to Mr. Harper then Prime Minister of Canada to call for an inquiry. Still, he remains steadfast against it.

An incomplete list of women and girls who have vanished or been murdered

RCMP Report Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women

Dr. Sarah Hunt What Should Be Done

Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women in Canada

Sign the Liberal’s petition calling for a Federal inquiry into Missing and Murdered women

http://youtu.be/dBPo9FgRBj4 Missing and Murdered Aboriginal women in Canada video by grade 11 students.

-

Sunday LIVING INTO THE FUTURE

Ottawa River Sunset Over the summer, a technique I learned about in a course was how to live into your future.

We started with setting a date we want to accomplish something, and then you reverse engineer what you hope to accomplish by that date backwards until you reach today’s date.

For example, my friend Wants an organic orchard on his land not too far for from here. He asked me how can he accomplish this using this method? I gave him these steps to follow.

- Create your team. His team is a horticulturist, seed supplier, and a friend who has an orchard near Niagara Falls. He needs at least six members on his team.

- Meet with the team assign tasks and a system for measuring accountability.

- Map what needs to be done each week until you reached the specific date of completion.

- Visualize walking through the orchard look at the details how does the soil underneath your shoes feel is there a scent on the trees. I always have problems with this type of exercise because I have aphantasia, which means I can’t visualize images in my mind, but I can experience the feeling I want. Our brain does not know what is real or imagined, what feeling does a walk through your orchard give you I asked him?

-

-

Inner Peace is in You

Discover Inner Peace 2022 March 13

It was after reading a friend’s Facebook page post it prompted me to write this blog post. Paul is a mediator and his words helped me focus on this piece. Thank you for your wisdom, Paul.

My garden Inner peace comes from a relationship that is based on acceptance, intimacy, and curiosity. Like a garden we need to weed out what does not serve us, and cultivate beauty, resilience,and strength. Sometimes this requires a change in perspective.

The late Zen Master, Thich Hanh Often wrote that peace should not be possessed, it should be a catalyst to help others suffering to discover peace.

As a long time, meditator, I am comfortable exploring my feelings in meditation. To know yourself more fully, explore with wonder each layer of who you are. My meditation practice became a lifeline after a brain injury a few years ago.

In 2018, I was diagnosed with left side neglect ((ischaemic right brain stroke during surgery, which meant at first , my brain could not recognize objects on my left side. I approached my brain injury with curiosity.

This injury led me to change my diet and empowered me to respond to a new version of who I am. I spent many hours researching the brain, reading, and listening to podcasts on neurology.

My first thought was not why me, but how interesting is it that our brain works like this. I was really intrigued. It was not easy but I persevered, and made peace with what happened by understanding what happened in my brain. One can always reconcile a negative event with a positive perspective. It helps the process to have the right question or statements of inquiry that will lead you to peace.

There is no right or wrong way of discovery. You’ll know it when it happens. I have found the key to peace is acceptance. Paul added the following steps, It is not verbatim. Meditate on these statements; to create a new perspective.

- I create my reality (trust). This perspective becomes available once we are aware of cause and effect.

- I am choosing what is happening (trust). Seeing ourselves as being endlessly creative.

- I welcome what is here (accepting our current experience).

- Appreciating physical sensations (intimacy). Appreciating the physical sensations in our body right now invigorates and increases the intensity of what we are experiencing. Think about eating your favorite food. When we slow down and taste each bite we feel more.

- I am the entirety of what I am experiencing (intimacy). What I am experiencing is creating the sense of me.

- Viewing life as being connect to all. (Cause and effect.,we are all connected) A flower does not exist without rain,sun and wind.

- I don’t know what I’m experiencing (Curiosity). Letting go of all ideas and labels about what it is we are experiencing. Looking at life as if we were a newborn baby seeing things for the first time. (wonder)

- I don’t know what I am. Creates space for possibilities.

- I experience a sense of excitement about what is about to happen next. Discovery of endless possibilities.

Discovering your way to a peace is not easy, we all have our own pain, sorrows, and fears. Give yourself time and space to embrace and recognize how you’re suffering. Be compassionate and gentle when,Starting an inquiry to self. However, remember there’s no right or wrong way to do this.

My meditation space/sauna -

Luezan Tue called Our Name

My family were environmentalists well before the term became popularized.

We are Denesuline people, from Northern Saskatchewan. We are strong, proud. Stewards, of Mother Earth. We take this responsibility seriously.

In the 70’s our dad answered the call of the land, and took his older children, to our traditional hunting lands. They hadn’t been back there for over 40 Decades until last summer of 2021. This is my dad’s legacy.

He answered the calling of the traditional lands, Luezan Tue, and inspired four generations to return to Djeskelni. He passed his baton to the next generation. He reaffirmed our sacred connection to the land. Everyone he took back to the land were transformed and carries the calling deep within their spirit.

In August, 2021, a small group of about of 17 family members went back to our land, organized by my nephew, Donald Deranger, who had gone there with Baba in the 1970s. They went to spread my late brother Patrick’s ashes around the lake to fulfill his last wish.It is clear to me that Patrick’s death facilitated a renewed interest back to our traditional land. The family answered the calling to return to the land. It is difficult to deny how powerful this spiritual calling is.

FAMILY MISSION

- Increase the quality of life for seven generations by building upon our rich Denesuline traditional heritage based on being stewards of the land, lending a helping hand, and create business ventures to generate profits and financial independence. Our family embodies Dene cultural tradition the pillars of which is respect, and to honour the teachings of our ancestors.

My family, like most Indigenous families, is complicated, affected by intergenerational trauma of colonialism, and residential school.

We have sometimes temporarily lost sight of family, our connection to each other and the spirit of our traditional lands. We are easily triggered and often will cut off one another from our life.

That said, I adore my Dene family, dysfunctions and all.

I read somewhere when you change the beginning of your story it changes the end of the story.

After I wrote this blog piece I went back and changed the beginning of our story.

I remain hopeful for the next seven generations. That they will continue to answer the call of our traditional lands. I see renewed interest in some of my nephews and nieces. The calling is strong in them, and I am hopeful.

Family Dene Camp 2021

Djeskelni Bech’anie Decheny’ah Camp, on the south shore of Luezan Tue within the southwest region of the Etthen Edeli dialect region, about 40 miles south of Tu Cho,

3 generations, my nephew Donald Deranger, his son, and grandchild.

Sand dunes on our traditional lands

Older sisters preparing wild meat from our land for the feast.

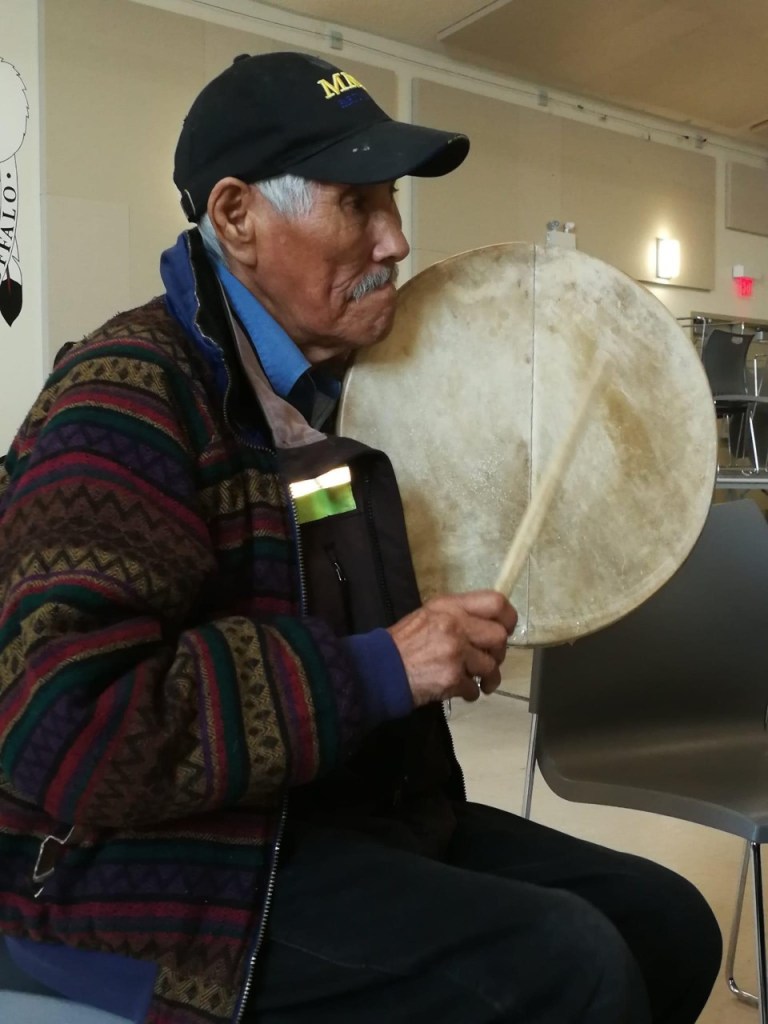

Brother-in-law John Mercredi (not at the camp) when you listen closely to Dene drum you hear the heartbeat of the land. Acknowledgment

My brother, Roger for keeping traditional prophecies of the Denesuline alive.

My nephew Donald Deranger for holding the baton for the next generations, and last, but so important, my late brother Patrick, a sacred pipe holder for passing the baton to his daughter when he gave her the sacred responsibility and honour of spreading his ashes on our traditional land.

Patrick Deranger -

2022 striding into the new year with eyes wide open

My intention in 2022 is not about losing weight although I could stand to lose a few pounds, it is not about exercising more. I could do more of that too.

My intention, my goal for 2022 is to not live small, to show up in life because my actions matter and the people in my life deserve to see the very best version of myself, Which is to show up in service to indigenous peoples struggling with addressing their trauma.

The next Being a Leader course starts in January 2022. If your interested in creating the best life for yourself connect with Tanyss Munro tanyssmunro@gmail.com 2022 I will continue my journey of growth and transformation, particularly as it pertains to my foundation Seventh Generation Indigenous Foundation and Training. (G.I.F.T) I’m really excited To be part of a group of extraordinary humans on the foundation. Our vision has capabilities to be a game changer in the delivery of services to indigenous communities across Alberta.

First, I am excited to confirm renowned physician and expert on trauma Dr. Gabor Mate has agreed to support GIFT foundation in the capacity as advisor to our curriculum writers. secondly, we start the new year by inviting additional board members who hold expertise in the areas of psychology, sociology,, law, and curriculum development.

My late dad, Isidore and older brother Fred Deranger -

January 1, 2022!

Living on the river shore is captivating, every day there is something phenomenal happening on the river, the neighbors made a ice rink over the weekend. -

DENE WAYS

Oral Tradition — The Living Heartbeat of Our Denesuline Culture

“Myths are public dreams, and dreams are private myths.” – Joseph Campbell

In this chapter, I write about oral tradition as the heartbeat of our Denesuline culture.

Oral traditions are the living foundation of who we are. Long before our people read or write, we were masterful historians, philosophers, and scientists of the land. We passed knowledge from Elder to child. It went from heart to heart and voice to spirit. These stories were never just entertainment. They were teachings: our law, our maps, our medicine.

In our family, storytelling was sacred. As a child, I would sit quietly, listening as my older siblings and elders spoke late into the night. They told of how the world came to be. They shared how to live in balance with the land. They also spoke of the prophecies that guided our people through times of darkness. We listened with our whole being. To interrupt was not just rude — it was to risk missing a thread of sacred knowledge.

Roger and Peter, my brothers, were a keepers of the Dene prophecies. They told stories that had been passed down through generations. These stories spoke of times when the land would change. They described how we would survive. Peter taught us through his humor, his presence, and his firm belief in our teachings. Dora kept the language alive by insisting we speak Dene in our conversations. She grounded us in the rhythm of our ancestors’ tongues. Annie, with her generosity and kind nature passed on stories through food and stories of our grandparents.. Each sibling held a different strand of the web. Together, they taught me that oral tradition is not only spoken. It is lived.

Our language is key to these traditions. Dene is not just a way of speaking, but a way of being. It expresses things English can’t. We are not separate from nature — we are part of it. To speak Dene is to understand your place in the world in a deeply relational way. Colonial systems sought to erase our language. They were not just stealing words. They were severing our connection to the world. And yet, in our home, the language endured. Even now, I speak it proudly, knowing that each word carries the breath of my ancestors.

I often think about how our mother, Therese, knew exactly when a story needed to be told. She never said, “Let me teach you something.” She simply began. By the time she finished, the lesson was planted like a seed. That is the Dene way.

When my son Andrew was a baby, my mom came to visit us. We set up a camera in front of her as she beaded. From time to time, she would tell a story or share a memory. Those moments were quiet, beautiful, and precious — her voice offering teachings in the most natural way. Knowledge was passed down like this: not forced, not formal, but flowing like a river through daily life.

Even today, I carry the rhythm of those teachings in my voice. Whether I am writing, speaking to youth, or sharing knowledge, I know the stories flow through me. They are not mine alone. They belong to all of us.

I do not partake in Cree ceremonies like sweats, and neither did my parents. My mother and father never participated in sweat ceremonies. They said it was not the Dene way. Our teachings came through story, through language, and through daily living — not through that particular practice.

The teachings of the Dene, when first spoken, are not always clear. As children, we listened, but we did not always understand. With time and experience, the lessons revealed themselves. A story told at ten years old carried one meaning; the same story told at thirty carried another. This is the way knowledge deepens, unfolding like layers over a lifetime.

This is how we remember who we are. This is how we survive. my brother Freddy with my dad Isidore Deranger

We are the stories. And we are the tellers.

-

Mama

Mama: Matriarch of Strength (1919–2016)

“What I think is that a good life is one hero journey after another. Over and over again, you are called to the realm of adventure, you are called to new horizons. Each time, there is the same problem: do I dare? And then if you do dare, the dangers are there, and the help also, and the fulfillment or the fiasco. There’s always the possibility of fiasco. But there’s also the possibility of bliss.” — Joseph Campbell

In this chapter, I write about the matriarch of our family, my mother, Therese Deranger (née Adams). She succeeded in keeping our enormous family of sixteen children together. She also cared for nieces and nephews who were raised as siblings. She was our anchor, our teacher, and our source of strength.

Mama was born on May 8, 1919, in Old Fort, Alberta. It was a time and place where survival depended on hard work. Community and a deep connection to the land were also essential. She married young—at only fifteen—and began raising children in a world marked by poverty and resilience. Her life was challenging. Yet, she carried her burdens with grace, humor, and a quiet strength. This shaped every one of us.

She endured much hardship. She raised sixteen children with limited resources. She faced the grief of losing six of them. Later, she survived breast cancer and multiple surgeries. Still, Mama never wavered in her faith or her responsibilities. She believed in perseverance, in doing what needed to be done, and in finding small joys even amid struggle.

Mama was strict. She was even loud and bossy.

My brother Billy once joked as he walked into the house. He said, “Mama, I can hear you all the way at Mah’s cafe.” Her discipline kept the household in order. She balanced authority with creativity.

She was a master at crafting beautiful designs that carried on Dene tradition. Her bead work was more than art. It was a language. Each stitch was a story. Each pattern was a connection to our ancestors.

Though she had her sharp edges, Mama’s care for others was undeniable. She welcomed not only her children into her home but also extended family and visitors. She ensured no one was left without a place. Our house was often chaotic, filled with noise, laughter, and sometimes tears, but it was also filled with love.

Mama was not one for outward displays of affection. It was at least not in the way one can imagine.” In fact, I never viewed my parents’ marriage as romantic. . Their love was practical, steadfast, and lived out in their commitment to raising a family and surviving together. It was, in its own way, a story of endurance and devotion rather than passion.

What stands out most is Mama’s resilience. She can withstand challenges that would have broken others. She did so while raising a generation rooted in both tradition and adaptation. She taught us strength, discipline, and faith, but also laughter and storytelling.

Mama’s journey was one of constant calls to adventure—whether in the form of survival, motherhood, or healing. She faced the dangers, and the joys with the courage of a true heroine. Her legacy is not only in her children and grandchildren. It is also in the values she instilled: perseverance, creativity, generosity, and an unshakable belief in family.

Her story is not one of perfection but of power. And it is a reminder that heroism can be found not just in epic battles or great journeys. It is also in the everyday act of keeping a family together. It is in holding fast to tradition. It is about daring, always, to endure.

In 1945 and 1951, tragedy struck. Over a decade before I was born, my brother Alfred, only fourteen, fell ill. He was sent to the hospital in Fort Smith, NWT. She never saw him again they didn’t return his body to her making her grieve that much harder. Six years later, in 1951, tragedy struck again when my brother Donald drowned in Lake Athabasca.

Mama took this loss very hard. Grief overwhelmed her to the point that she suffered a nervous breakdown after Donald died.

Carrying her sorrow, she gathered the family and moved us to Uranium City, Saskatchewan, to be closer to her parents. It was an act of survival—seeking the comfort of kin, grounding herself in the familiar when life felt unbearable.

For ten years, Uranium City became our home. But in 1961, Mama made the decision to return us to Fort Chipewyan, carrying both her grief and her determination. This journey back was more than a relocation—it was an act of reclamation.

-

Rose — Survivor with an Indomitable Spirit

“In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.” — Albert Camus

In this chapter, I write about my sister Rose, the strongest person I know. She is dynamic, fearless, and deeply committed to protecting both people and the land. Her life has been marked by struggles. No one should ever have to endure these struggles. Yet, she carries herself with courage, compassion, and a fire that refuses to be extinguished.

I remember once driving her to Parliament Hill in Ottawa. She wanted to protest what was happening to the land. She was concerned about the people living downstream from Fort McMurray. She was the lone protester, undeterred by being just one voice among many. She walked straight up to the RCMP officers. She asked if it was okay for her to protest on the Hill. They asked how many people were with her. “Just me,” she replied without hesitation. They smiled and said, “Yes, and anyone else who wants to join you is welcome.” That was Rose. She stood her ground and was fearless. She was willing to carry the weight of justice on her own shoulders if necessary.

Rose has always cared deeply for the underdog, for those who had no voice. She has endured unimaginable hardship, yet she has always kept her heart open. She cares for people fiercely, and I know she cares for me.

When she was sent to Indian residential school, her defiance and strong spirit made her a target. She refused to be broken. Her attitude led to her being transferred to the Alberta Hospital, a mental institution. Not because she was mentally ill, but because they thought it was the only way to crush her spirit. There, she was subjected to electric shock therapy, one of the cruelest tools used to break children. But they failed.

Our older brother Freddy went directly to the Alberta Hospital and secured her release. Still, the trauma she endured could have destroyed her. Instead, she survived. She came through those horrors determined to live fully, to claim her dignity, and to build a meaningful life.

Rose went on to graduate from university and became a teacher in northern communities. She carried her strength into classrooms, giving young Indigenous children hope, encouragement, and a reflection of their own resilience. She taught not only lessons in reading and writing, but also lessons in survival, healing, and cultural pride.

She has carried heavy burdens, but she has also carried light. She is a matriarch in every sense. Her life a testimony to what survival means: not just to endure, but to transform pain into power.

Rose is a survivor with an indomitable spirit. She reminds me, and all who know her, that survival is not about merely staying alive. It is about refusing to let the forces of destruction define who we are. She stood against systems meant to silence her, and she emerged as a voice, a teacher, and a warrior.

Her story is not just her own. It is the story of our people: resilient, unbroken, and still here.

-

FREEING EGO

“Life will offer you with people and circumstances to reveal where you’re not free.” — Peter Crone

“Nothing is either good or bad; it is thinking that makes it so.” — William ShakespeareIn this chapter, I write about the lifelong work of freeing myself from ego. This is the voice that seeks validation. It clings to identity. It whispers that I am only enough if others say so.

My insights come from listening—to podcasts, music, spiritual teachers, and life itself. I share because I want others to know: this is a path worth walking.

When we feel hurt or wronged, it’s natural to ask: Why am I reacting this way? Often, unresolved childhood trauma erupts. It interprets a current moment as a familiar story from our past. This is not the truth of what’s happening now.

As Dr. Gabor Maté recounts, even a minor disappointment can trigger a disproportionate response:

“I land at the airport … ‘Never mind’—I take a taxi home. I arrive home … I don’t even talk. I just grunt at her … most of me is in the grips of the distant past. This physio–emotional time-warp … is one of the imprints of trauma.”【3】

His words are a powerful reminder: even deeply wise people can be hijacked by old wounds. Ego seizes the narrative, and for a moment, the witness slips away.

When I feel triggered, I pause and ask: What is this moment teaching me—humility, empathy, the need to let go? It’s taken years of meditation. Buddhist spiritual practice helped. My own Dene teachings guided me. I now recognize ego as a passing shadow. It is not who I truly am.

A friend once asked me, “Do you want to be right or do you want to be happy?” That question stays with me. Choosing happiness over being right opens space to forgive. It opens space to understand. It allows me to reclaim power—not over others, but over my own reactions.

For example: someone doesn’t return my call. My ego spins a story—they don’t care, they don’t respect me. But maybe they missed my message or got busy. The ego, not the event, created my suffering. Realizing that—the upset is mine—means I can choose differently.

Ego says, “You must be right.” Spirit says, “You can be free.” Owning 100% responsibility for our reactions restores agency. If our happiness relies on others, we’ll always feel powerless.

Dene teachings remind us to walk humbly—we don’t own the land, we belong to it. Buddhism teaches us that clinging is the cause of suffering, and letting go is the path to peace. If we merge these teachings, freeing ego is less about erasing identity and more about remembering our belonging.

I ask this again, both to myself and to you. Do you want to be right? Or do you want to be free? That question is my compass, again and again.

-

Tea four Two

In this chapter, I invite you to consider a simple yet meaningful gesture—inviting your best friend for a beverage. It could be tea, coffee, a glass of wine—whatever you both enjoy. The key is to set an intention and schedule it in advance, ensuring you are mindful and fully present. No TV. No phones. No distractions. Just you and your friend.

Picture a quiet afternoon where the focus is on connection. The conversation moves beyond small talk into genuine listening and heartfelt sharing. Such moments can deepen bonds and become rituals we truly cherish.

When I prepare for my tea with Maggie, I begin with a Japanese tea ceremony to make our matcha. Using a bamboo whisk, I move slowly back and forth until the tea becomes frothy. As I do this, the earthy aroma fills the air and the deep green color catches my eye. Instantly, I am transported to a calm and joyful state, fully present in the moment. I find satisfaction in the simple act of making tea. I know that the intention and care I put into it will carry into the next moments. This is the flow state—where joy naturally unfolds.

My friend Maggie and I have been sharing virtual tea for years because we live in different provinces. We catch up on her children, her work, and her parents. Both Maggie and I love tea. Matcha is our favorite. Its rich, smooth flavor seems to make our conversations feel even more special.

It’s in these moments. Whether in person or across the miles, we remember the joy of simply being here for one another. That is the true essence of connection.

-

HUMAN SPIRIT

Human beings are inherently social. A sense of belonging is a basic psychological need. Whether through relationships, family, or work, our connections to others shape our identity and well-being. In Japanese culture, there is a concept called ikigai—meaning “reason for being.” It describes the intersection of purpose, passion, and fulfillment.

I attended Holy Angels Indian Residential School, located in a small hamlet in Alberta, for seven years. I know that cultural genocide is real. The goal of these schools was to destroy Indigenous culture and identity, and in many ways, they almost succeeded.

I was spared some of the abuse. I never experienced sexual or emotional harm. However, some of my siblings and classmates were not so fortunate. I remember sitting in the front row with my brothers, who carried untold trauma from their time there.

Years later, I became a university student studying Culture and Arts at the University of Warsaw. During this time, I visited historical sites across Europe. One day, I stood in Auschwitz, in the place where Holocaust victims were once gassed in the showers. Overwhelmed, I stepped away from the group and sat outside, crying. It was a moment that has never left me. I asked myself: How can humans be so cruel?

The extermination policies of the Nazi regime systematically murdered millions—Jews, Roma, disabled people, and others deemed “undesirable.” The survivors bore deep psychological wounds, yet many found purpose in ensuring the world never forgets. Psychiatrist Viktor Frankl was himself a Holocaust survivor. He wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning about human choice. Even in the most dehumanizing conditions, human beings can choose their response. He believed that meaning could be found even in suffering, and that this search for meaning is what allows the human spirit to endure.

I recognized this truth in my own journey and in the resilience of my people. The residential school system, like the camps Frankl survived, was designed to strip away identity, dignity, and hope. Just as Frankl found a renewed purpose to help others in finding meaning, many Indigenous people have regained their languages. They have also reclaimed their ceremonies. They have revived their traditions as a way of saying: We are still here.

Frankl taught that when we can no longer change our circumstances, we are challenged to change ourselves. That teaching has guided me through my own healing and shaped my ikigai—my reason for being. Despite what was taken from us, we continue to live with intention so future generations will thrive.

My time in the residential school system and what I saw in Europe shaped my understanding of trauma. These experiences also influenced my perception of human behavior. These experiences gave me a lifelong commitment to address the lasting impact of such suffering.

For several years, I served on the board of the Nechi Institute: Centre of Indigenous Learning. I eventually became Chairperson before stepping down in 2021. Soon after, I founded the Seventh Generation Indigenous Foundation and Training (GIFT) www.seventhgift.ca, a charitable organization focused on addressing addiction and trauma in First Nations communities through land-based cultural teachings.

Through these personal experiences, I discovered my ikigai: to support those healing from trauma and addiction. Today, I continue that work through my Empathetic Witness podcast, keeping the conversation alive.

My guiding principle—my ikigai—is simple: to help others heal.

-

A Journey to Australia: 2008 Beauty, and the Shared Grief of Stolen Children

picture of my niece, elder Summer, Daniel, Nanton, Australia has always held a special place in my heart. Though it’s a 27-hour trip from Ottawa, I’ve been fortunate to walk on that beautiful land four times. Each visit has left a lasting impression. Yet, this particular journey was different. It was deeply personal, profoundly emotional, and soul-stirring in unexpected ways.

My husband, our son Andrew, and I traveled together to visit my late niece, Margaret Ann. I was also scheduled to speak at a conference. But, the time we spent together as a family is what has stayed with me most. The experiences we shared are unforgettable.

A Sacred Sanctuary and a Scenic Drive

A friend who now lives in Melbourne suggested we visit William Ricketts Sanctuary, nestled in the lush Dandenong Ranges. After a brunch of salmon omelets, lovingly prepared by my husband, we set off. Renting an apartment for our stay turned out to be a brilliant idea. On an earlier trip, we had stayed on a houseboat along the Murray River. That was another unforgettable experience.

The drive was serene and enchanting. Raised in Scotland, my husband had no trouble adjusting to the left-hand side of the road. Towering ferns lined the highway, creating a dreamlike landscape that whispered with the presence of something ancient and wise.

Though the sanctuary was inexplicably closed on a blue-sky day, we returned the next day. Along the way, we discovered Tea Leaves, a shop in Sassafras with over 300 varieties of tea and herbs. For a tea lover like me, it was heaven on earth. www.tealeaves.com.au

From Rainforest Wonder to Emotional Reckoning

Later, we visited the Melbourne Museum. We began in the rainforest exhibit, small but delightful, then watched Dinosaurs 3D at the IMAX — an awe-inspiring experience. But what moved us most deeply was the exhibition titled:

“I Am the Land: The Land is Me”

Link to exhibit →This profoundly thought-provoking display centers on Australia’s Stolen Generations. Thousands of Aboriginal children were forcibly taken from their families between 1910 and the 1970s. This occurred under government-sanctioned assimilation policies. These children were placed in institutions or foster care, forbidden to speak their language or practice their culture. Many suffered abuse. Families were torn apart for generations.

Halfway through, I had to stop. I was overwhelmed. The grief in the room was palpable — ancestral, enduring.

My son Andrew sat on a bench next to a statue of two children being taken from their mother. He sat silently, his head in his hands. Seeing him there, next to those children, with the words of a grieving mother etched beside them, was heartbreaking.

I asked him what he was thinking. He looked up, tears in his eyes, and asked:

“How old were they when they were taken? Why?”

I had no answer that made sense of such injustice. All I say was: “It should never have happened.”A Personal Echo of a Collective Pain

What I was feeling in that moment wasn’t only empathy — it was resonance. I am a survivor of Canada’s Indian Residential School system, where I spent seven years. My trauma met theirs in that space. And maybe Andrew, in his quiet sorrow, was feeling the inherited weight of intergenerational trauma.

In Canada, from the 1870s until 1996, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their homes. They were placed in residential schools. Most of these schools were run by churches under federal policy. These children, like those in Australia, were forbidden to speak their language or see their families. Thousands never returned. Abuse was rampant. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission later called it what it was: cultural genocide.

Grief Across Continents — and a Path Ahead

What struck me most was how pain is shared — across continents, across cultures, and across time. Though I stood on foreign soil, the story was achingly familiar. The systems were different, but the wound was the same.

And yet, there is power in witnessing. There is healing in remembering. There is dignity in telling the truth.

Our children need to know these stories. We need to hold space for the grief, and just as importantly, for the resilience. Because as Indigenous peoples — in Australia, in Canada, and around the world — we are still here. We are remembering. We are healing.

-

Indigenous Healing A book review

Indigenous Healing, by Rupert Ross – A Review by Angelina

I saw that a package had arrived on the counter. I touched the package and observed it was soft and about the size of a paperback. I thought that it contained a book. I was curious but, since it was not addressed to me, I set it aside. A couple of days later, I noticed the package was opened. Next to it was Indigenous Healing, exploring Traditional paths.

A book by Rupert Ross! I was so excited, because I am familiar with his writing, and I find his writings to be thoughtful. Well organized, and authentic.

I have also had several long discussions with him about his work as a prosecutor. This work has had an emotional impact on him. I knew without reservation it would be a well-written book. This response is certainly different from the one I originally had. Over 20 years ago, when I was offered his first book to read, Dancing with a Ghost, I felt differently. Back then, I didn’t know Rupert. He is an exceptional kind man, and I am proud to consider him my friend.

I am certain that writing a book as a non-Indigenous person on Indigenous spirituality and culture has its burdens. You have to be exceptionally meticulous that no white privilege bias seeps through. Additionally, you must acknowledge that your knowledge does not come from any experience as an Indigenous person. This is a shortfall. But what happens when most of your experiences comes from prosecuting Indigenous peoples? That certainly does give one a negative view of those peoples. You don’t exactly meet them in the best circumstances.

The dysfunction and chaos of remote Indigenous communities cause people to be in court before him. He served as a prosecutor. As a prosecutor, he was astounded by the level of violence he saw. He chose to engage with the Indigenous communities he served. He wanted to understand why they were producing so much tragedy. He also wanted to do what he can to help. Ross is fortunate. He encountered many Indigenous people, both men and women, who were willing to teach him. He was open to learning from them.

His books are not disingenuous. He understands the complexities of these traumas. He knows that the loss of traditional knowledge is a significant contributing factor. The history of residential schools is also a huge part of this dysfunction. To get to this understanding, you have to be a compassionate human. You also need to be a skillful and empathic listener. He obviously possesses these qualities. This is very obvious from the observations in his books. I got so excited to see a new book by him. I not wait to get started on reading it.

Rupert does not have a single prejudiced bone in his body. This is true even after 26 years as a prosecutor. He has seen the worst that humans can do to each other.

I quickly devoured the first half of the book. It does not disappoint. Reading the book felt like visiting with an old friend. It was like talking about other old friends. He cites a lot of the same people I know from my own work on indigenous healing. He expertly describes the layers and nuances. He reveals the underlying foundation of indigenous knowledge. This is impressive, especially for a non-indigenous person, I add. Someone once described his writing as revealing to themselves who she was as an indigenous woman. Indeed, his writing does give one pause to say: “Aha!”, “That is me”, or “that is my belief! He writes authoritatively, and you don’t get any feeling that he is being disingenuous or flippant in his observations. His respect for indigenous spirituality and knowledge is unmistakable.

Ross cleverly begins this book. He describes the Indigenous worldview. He explains our spiritual connection to the land and all living things on it. He further explains peripherally about the medicine wheel. He discusses the significance it has. He draws a correlation between it and Indigenous cultural relevance to everyday life. For me, that was an excellent place to start. It sets the foundation for how you would view the rest of the book. By acknowledging and emphasizing the Indigenous worldview, one can comprehend the chaos and dysfunction. This perspective led to the disempowerment of Indigenous peoples. This understanding allows for a greater appreciation of Indigenous peoples. It also fosters genuine respect for their culture.

I had to take the second part of the book more gradually. This was due to how he described the trauma experienced by former residential school “survivors”. This really hit home. It was not because I had experienced any abuse when I was in residential school. It was because I can empathize with the children who did. I had to take many breaks because my eyes would burn from tears that were difficult to hold back. I stopped reading. It brought up thoughts about close family members who experienced similar trauma while in the same residential school. Some of them are no longer with us.

Finally, Ross identifies how our Indigenous worldview is key to success in some healing modalities. This is especially true in Indigenous communities. In other words, to acknowledge our cultural place in time and space is the best way towards healing. And we must embrace it. We must embrace the teachings of our ancestors. That is where our power lies.

Who should read this book? If you are an Indigenous person, or even know one, I highly recommend this book. It is also recommended for students, lawyers, or other professionals who work for and with Indigenous communities. my mom and late brother Pat/

-

From Grief to Action: Fight Against Addiction

I dropped a tear in the ocean. The day it is found is the day I will stop missing you. – Unknown

It shattered my world when you died. The world as I knew it changed forever in an instant. Tears cascaded down my face as I try to process that your beautiful spirit is on its final journey home. RIP Connie your struggle is over, it is up to us to continue the fight. Connie was a kind person with a bright smile and a loving heart.

I got news yesterday of her passing into the Dene spirit world. The last few weeks before her death, I spoke to her once. She was trying her best. She was accepting the grief of Annie’s passing. Annie was her mom and my sister. Annie passed on December 25, 2025. We cried together.

On her last day on earth, she spent the afternoon at a celebration of life for her mother-in-law. Grieving two matriarchal women so close together must have been unbearable pain. She inspired me in many ways. Her strength stood out. She stood up for what she believed in, and It cost her her job as a bookkeeper. I feel she never completely recovered from it. But she didn’t complain.

When did all the pain start? Was it because of residential schools? Was it the loss of our Indigenous language and traditional lifestyle? Is it intergenerational trauma?

It’s important to honour the lives of those we’ve lost. We can do this by advocating for change. We should also support initiatives like the 7th Generation Indigenous Foundation and Training. Your commitment to addressing the opioid crisis and the impact of alcoholism is commendable. Raising awareness and fostering community support can make a significant difference for future generation.

Now more than ever, we must emphasize prevention and build capacity within our communities. We have the means to do it with your help.

In 2022, I founded the 7th Generation Indigenous Foundation and Training (GIFT). You can read about our mission on the website. Each course we develop costs $10,000 and is tailored to the community’s needs, deeply rooted in cultural values. Visit seventhgift.ca for more information.

Connie was a kind person with a bright smile and a loving heart. here with family sharing a meal

Your donation to the 7th Generation Indigenous Foundation and Training (GIFT) goes beyond supporting a cause. It invests in the lives of countless individuals. These people are fighting against the devastating grip of addiction. Your support will help develop culturally relevant programs that empower our communities, offering hope, healing, and a path to recovery.

Together, we can break the cycle of addiction and trauma that has plagued our families for far too long. Every dollar you contribute helps to build a supportive environment. This is where our children can thrive, free from the shadows of addiction. Let us honor Connie’s memory by ensuring that her struggle is not in vain.

Join us in this vital mission. Donate today and be part of the solution. Together, we can create a legacy of healing and hope for the next seven generations. Your generosity can change lives and save futures. Let’s stand together and make a difference.

-

Embracing Nature: A Dene Perspective

my dad, Isidore Deranger with my older brother Freddy.

Indigenous teachings hold significant value in today’s world, offering profound insights into sustainability, community, and respect for nature. These teachings emphasize a deep connection to the land.

They foster a holistic understanding of life that can guide us in addressing contemporary challenges. By prioritizing these traditions, we can foster greater environmental stewardship, enhance community resilience, and cultivate a more inclusive society. Embracing indigenous wisdom honors the rich cultural heritage of these communities.I have always been connected to nature; it is in my DNA and is who I am as a Dene. My father was a hunter and trapper. He danced with nature in synchronicity with the natural flow of the seasons. His life depended on this cohesive interdependence, and he respected that he was helpless against Mother Nature.

It also provides us with essential lessons for living harmoniously with our environment and each other. Recognizing and implementing these teachings is crucial for achieving a more equitable and sustainable future.

I have always been connected to nature; it is in my DNA and is who I am as a Dene.

My father was a hunter and trapper. He danced with nature in synchronicity with the natural flow of the seasons. His life depended on this cohesive interdependence, and he respected that he was helpless against Mother Nature.

My life overall is far removed from my parents’ hunting and trapping lifestyle. I live a comfortable life with modern conveniences. That said, I still talk to the trees. I also talk to the plants. I whisper thanks to water just before I drink it. This connection to nature is integral to my identity. It reflects the teachings passed down from my father. He understood the delicate balance of life.

Even in my modern life, I keep that sacred relationship with the natural world. Embracing these practices fosters a sense of gratitude and awareness. They remind us of the significance of nurturing our bond with nature. This is important regardless of the lifestyle we lead.

He once told me about a violent storm on Lake Athabasca. He had to go ashore for 4 days until the storm passed. He was prepared and brought enough supplies to last him. He had tea and cooked bannock over fire and drank his tea under the stars.

My brother on Lake Athabasca 2022.

My life overall is far removed from my parents’ hunting and trapping lifestyle. I live a comfortable life with modern conveniences. I still talk to the trees and to the plants. I whisper thanks to water just before I drink it. A connection to nature is a profound part of my identity. It reflects the teachings passed down from my father. He understood the delicate balance of life.

Even in my modern life, I maintain that sacred relationship with the natural world. Embracing these practices fosters a sense of gratitude and awareness. They remind us all of the importance of nurturing our bond with nature, regardless of the lifestyle we lead.

I keep in mind how Indian residential school period tried to rid me of my indigenous identity. by writing about it,I hope to keep it alive.

I have always been connected to nature; it is in my DNA and is who I am as a Dene. My father was a hunter and trapper. He danced with nature in synchronicity with the natural flow of the seasons. His life depended on this cohesive interdependence, and he respected that he was helpless against Mother Nature.

He once told me about a violent storm on Lake Athabasca. He had to take refuge ashore for four days. He stayed there until the storm passed. He was well-prepared. He had brought enough supplies to last him. He spent those days sipping tea under the stars. He also hunted small game.

I keep in mind how the Indian residential school period tried to erase my Indigenous identity. By writing about my experiences and heritage, I hope to keep that identity alive. My life overall is far removed from my parents’ hunting and trapping lifestyle. I live a comfortable life with modern conveniences. That said, I still talk to the trees and to the plants. I whisper thanks to water just before I drink it.

This connection to nature is a profound part of my identity. It reflects the teachings passed down from my father. He understood the delicate balance of life. Even in my modern life, I keep that sacred relationship with the natural world. Embracing these practices fosters a sense of gratitude and awareness. They remind us of the importance of nurturing our bond with nature. This holds true, regardless of the lifestyle we lead.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.